I Might Be Wrong (Part II)

"I find your arguments strewn with gaping defects in logic."

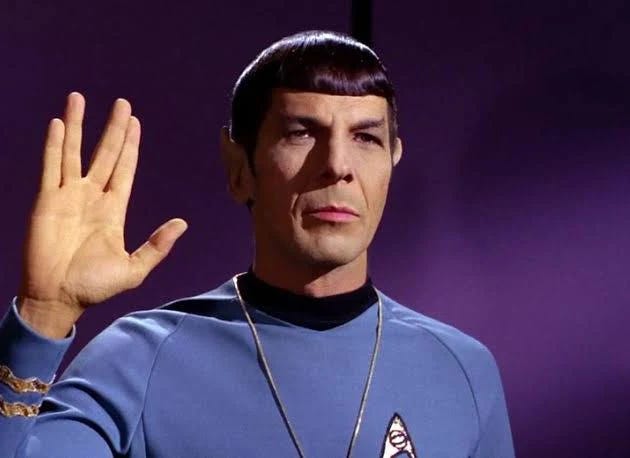

Some of my earliest memories are watching Star Trek with my Dad. (He was proud to say that he participated in the letter-writing campaign in the mid-1960s responsible for keeping Star Trek on air after NBC threatened to cancel the first season.) I was mostly a Next Generation Trekkie, but we also watched the original movies and Spock, with his devotion to reason and logic, was my favorite character. (It’s not a coincidence that my son’s full name is Leonard.) And there was a time, mostly in my twenties, when I genuinely believed that pure rational thought, untainted by irrationality or emotions, was possible. That if I could just think hard enough, and rationally enough, I could always come to the “right” conclusion. Now I can chuckle at this as cute and sophomoric. Because when you understand how the human brain works, you know this simply isn’t possible. But what I didn’t fully appreciate until recently, is that we might not want this “pure rationality” to be possible.

In the past few years I’ve read several books about the human brain and how it constructs our belief systems (for example, Michael Shermer’s The Believing Brain). Given how polarized our country is at the moment, I wanted to know how people come to believe the things they do. This led me to a fascination with conspiracy theories and how people fall susceptible to outlandish beliefs like the moon landing was a hoax or, at the most extreme, that shapeshifting lizard aliens control the earth. What surprised me most in this exploration is how I might have more in common with conspiracy theorists than I’d like to admit. Sometimes the divide between “us” rational thinkers and “those” irrational thinkers is much thinner than we’d hope.

For example, it prompted me to reconsider some of my ideas about health and nutrition and whether the evidence I had for those beliefs was as robust as I thought. For about a decade, I was pretty strict about my diet and fitness and obsessed with “optimizing” my lifestyle. You know–veganism is THE WAY, gluten is evil, and supplements can cure cancer. I’m only kinda exaggerating. I was pretty far down that rabbit hole. But, of course, I was only reading and consuming information that supported this perspective. I was not seeking out a variety of credible, peer-reviewed sources and weighing the evidence and considering the nuances of what we do and DO NOT KNOW about optimal human health. And it took having some kinda serious health issues to get me to reconsider these highly cherished beliefs. (That’s the short story.) So many of the mental foibles I have probably scoffed at conspiracy theorists for making, I have in fact made myself. And, actually, we ALL have, we ALL do, probably on a regular basis. And, according to Kathryn Schulz in Being Wrong, the fact that our brains are susceptible to (and perhaps “wired” for) some of these mental missteps is not completely a bad thing.

In order to understand why we make mistakes and are inclined to error, we need to understand how our minds work. Schulz presents this neuroscience and psychology research and emphasizes that the “flaws” in our brains that make us, for example, inclined to believe something based on specious evidence is precisely what makes our brain incredible and enabled our survival and progress as a species:

“I mean that believing things based on paltry evidence is the engine that drives the entire miraculous machinery of human cognition…the cognitive operating system we actually come with is suboptimal. It has no use for radical doubt. It does not rely on formal logic. It isn’t diligent about amassing evidence, still less so about counterevidence, and it couldn’t function without preconceived notions. It is eminently capable of getting things wrong. In short, our mind, in its default mode, doesn’t work anything like any of these [ideal] models. And yet--not despite but because of its aptitude for error--it works better than them all” (114-115).

When Schulz talks about “believing things based on paltry evidence” she’s referring to our inclination toward inductive reasoning–a strategy of “guessing based on past experience.” She walks the reader through several exercises that demonstrate how we do this automatically. In fact, it’s responsible for how we learn most things like language, categorization, causality, and psychology (120). Therefore, she states: “without inductive reasoning–the capacity to reach very big conclusions based on very little data–we would never gain that expertise. However slapdash it might initially seem, this best-guess style of reasoning is critical to human intelligence. In fact, these days, inductive reasoning is the leading candidate for actually being human intelligence” (121). But while our conclusions may be probabilistically true, that means that they can also be wrong (121).

All of this underscores why Schulz wants us to reconsider our relationship to error. It is far more complicated than to say logical reasoning gets things right and sloppy thinking gets things wrong, which is exactly what I thought, per Mr. Spock. Instead, we need to understand that the way of thinking that makes us right most of the time, is also what makes us wrong some of the time: “What makes us right is what makes us wrong” (Schulz 122).

This is an incredible paradox if ever there was one.

Now, I also understand that the point of Spock’s character was not to glorify reason and logic, but rather to complicate the logic/emotion binary and to show that one really can’t separate them. After all, Spock was part human, and he could no more untangle his humanness from his Vulcan-ness and then we can completely extract emotions from our understanding and experience of the world. And this emotional piece is one that I am especially interested in and hope to explore next time…

As always, thanks for reading!