The Democracy Lab (part I)

“Ruling ourselves has never been straightforward and never will be.”

In September I started a program called The Democracy Lab, which is conducted through the Wyoming Institute for Humanities Research here at the University of Wyoming. It’s a one (academic) year program that provides time, space and resources for a cohort of six UW faculty/staff and community members to explore questions about the quality of our democracy. We met every other week to practice Collaborative Communication, discuss provocative and quintessential American texts, learn how to write and publish an op-ed, and develop and complete our own research project that culminates in a public presentation (which took place two weeks ago and I’l share the recording when it’s available) and a written piece for the Democracy Lab journal (probably out in the fall). I haven’t been writing much here because I’ve been putting all my energy there. Now that it’s wrapping up and I’m working on my written piece, I’d like to share a reflection on this experience and my project.

First, I did this program because as much as I love my job teaching and working independently on this Substack and other essays, it’s hard to prioritize this kind of work without structure and deadlines and accountability. In addition to the bi-weekly meetings, the program granted me a course release in the spring so I could intentionally carve out time dedicated to reading and thinking. Also, to have a community to think with is invaluable and this was an incredibly kind, generous, and thoughtful group who listened to and tested my thinking for eight months.

We began by reading Astra Taylor’s book Democracy Doesn’t Exist But We’ll Miss It When It’s Gone which is structured around the inherent tensions built into our American democracy: freedom/equality, conflict/consensus, inclusion/exclusion, coercion/choice, spontaneity/structure, expertise/mass opinion, local/global, present/future. As I explained in my very first Substack, I think these paradoxical spaces are where the most fruitful, meaningful, challenging thinking and learning happens. But I don’t think most of our public conversations reside here; instead, they remain stuck in the superficial space of binary thinking, this or that. Either, for example, you are pro-life or pro-choice, pro-immigration or xenophobic, capitalist or communist, etc. Often the loudest pundits act like we can only hold one, simple idea in mind at a time. As if we can’t both want women to control their reproductive choices AND be seriously concerned with the life of a fetus. As if these aren’t hard, complicated issues that require us to honestly grapple with trade-offs and competing values/priorities.

The book was also helpful in grounding our thinking about democracy in its past and examining the ways the scope of democracy has shifted over time. Taylor reminds us that the word democracy comes from ancient Greece and simply means: “the people (demos) rule or hold the power (kratos).” But how that works—who counts as the people and how they rule—is perennially debated. This was clear in our last national election as both parties branded their side as the one to “save democracy.” But perhaps even more perplexing is Taylor’s suggestion that: “Democracy destabilizes its own legitimacy and purpose by design, subjecting its core components to continual examination and scrutiny.” This is what makes democracy hard, and, as Taylor points out, a system that doesn’t perfectly exist. Taylor writes: “Taking a more theoretical approach to democracy’s winding, thorny path and inherently paradoxical nature can also provide solace and reassurance. Ruling ourselves has never been straight-forward and never will be. Ever vexing and unpredictable, democracy is a process that involves endless reassessment and renewal, not an endpoint we reach before taking a rest.”

I’ve come to think that democracy’s paradoxical structure is what makes it wise; wisdom is born in hard spaces. I am skeptical of systems and solutions that offer easy solutions to hard problems, and a group of people (especially a diverse group of people that are not inherently united by a single ethnicity or religion or other identity) ruling themselves, together, may be the hardest of all. Truly an experiment. Of course, that makes it slow and difficult. It is not easy to pass laws or make changes because of how power is divided and the amount of consensus (and therefore argument and persuasion) that is required. But I am increasingly persuaded that that is exactly as it should be.

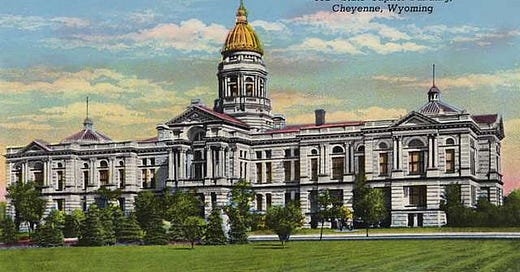

I have been concerned about democracy for a long time (regardless of who has been sitting in the Oval Office), and I was grateful to finally prioritize spending the time to think about it, to learn and/or re-learn what I forgot or never knew. So much of the process has been abstract or unclear to me and now I had the space to hash out these points of confusion. Perhaps the most powerful part of this education was when we visited the Wyoming Capitol in Cheyenne and the tensions we’d been reading and discussing came to life.

I was confronted with confounding facts and emotions–proud to be a resident of the first state to grant women the right to vote in 1869 (in fact, Wyoming’s statehood was almost denied for this reason; but they prevailed and Wyoming was designated the “Equality State”) and the first state to elect a female governor, Nellie Ross, in 1924—and yet, even one hundred years later, there hasn’t been another female governor. I was shocked at how open and accessible the building is—you can just walk in. No metal detectors, no signing in. Our guide told us that if you wanted to speak with your representative, you could have someone deliver a request and they would often come out of the chamber to speak with you. The governor was just walking around, not ensconced in insurmountable layers of security. Surely this is largely due to Wyoming’s small population, but I was buoyed by this accessibility. That said, if you are a minority in this solidly red (the reddest) state, all the access in the world to your representatives might not feel like enough.

The capitol building is beautiful and we learned about its history and architecture and renovations. Statues of the Four Sisters—Truth, Justice, Courage, and Hope—reign over the rotunda. The building is an impressive testament to Wyoming’s history and American ideals. But these virtues often feel to directly contradict the spirit of particular bills that were being debated on the floors of the house and senate. It was exciting to see the legislative process in action, to point out our representatives below us in the gallery—and frustrating. Depending on how one feels about what’s happening, it can be like watching a horror movie, squirming in anticipation of the next inevitable jump-scare.

All of this is to say that the experience of witnessing the democratic process is as inspiring as it is troubling. Or, as Taylor writes:

“The unsettling fact is that ruling ourselves is not a predictable or stable enterprise, but this is as much a cause for jubilation as despair. This seemingly fatal flaw is also the source of democracy’s strength. Its fragmentary, unfinished nature poses a challenge to all of us who want to be both equal and free.”

I wonder if part of our problem doing democracy is not that it is hard, but that we mistakenly believe it should be otherwise.

The main objective of the Democracy Lab was to pursue a substantial research project. When I applied, I did so thinking I’d pursue something to do with free speech and building on the work I’d been doing surrounding these issues on the UW campus. Once I was accepted, I thought maybe I’d do a project about James Baldwin, whose work I’d read in pieces sporadically, yet obsessively, over the years and longed to study more deeply. In addition, the political philosopher Hannah Arendt’s name and words kept confronting me in other contexts (usually in the form of some prescient quotation about totalitarianism) and piqued my curiosity.

I already admired Baldwin because of how he thought about love and politics. When I read Baldwin, it is like going to church. That is, it is a transcendent, enlightening, joyful, yet existentially hard experience. This isn’t a coincidence since he was raised by a preacher and became a preacher himself for a short time as a teenager until he became disillusioned by the hypocrisy he saw in his church when they did not take the call to “love thy enemy” seriously.

Baldwin writes in The Fire Next Time: “But what was the point, the purpose, of my salvation if it did not permit me to behave with love toward others, no matter how they behaved toward me? What others did was their responsibility, for which they would answer when the judgement trumpet sounded. But what I did was my responsibility, and I would have to answer, too.”

This resonates with me deeply. I was raised Christian and even as I started to drift away from the church, I was still compelled by Jesus’ teachings (loving thy neighbor as yourself, giving to the poor…). In fact, I often think I left the religion because I believed it. I longed for the beautiful words and wisdom, but couldn’t square that with the experience of church and Christian culture. Reading Baldwin feels like honest spiritual work; he wrote from a place of wise conviction and honest searching and grappling and humility. His questions cut across the social/political spheres. He did not draw a neat line between his personal salvation and human salvation. They were one and the same. As a civil rights activist, his fight was not just for political equality but spiritual well-being:

“I am concerned for their dignity, for the health of their souls, and must oppose any attempt that Negroes may make to do to others what has been done to them. I think I know—we see it around us every day—the spiritual wasteland to which that road leads. It is so simple a fact and one that is so hard, apparently, to grasp: Whoever debases others is debasing himself. That is not a mystical statement but a most realistic one.”

Black and white people needed one another, he wrote. And yet, he did not shy away from conveying the full weight, horror, and destruction of slavery and Jim Crow. He insisted that people confront this awful reality at the same time that he insisted the path forward, a true reckoning, was one that brought everyone together and recognized our inhuman interdependence. He loved Malcom Luther King, Jr. as well as he loved Malcolm X, though they hardly approached the civil rights struggle the same way. Baldwin did not close himself off to the ideas or people with whom he disagreed (another virtue that seems sorely lacking in public intellectuals today).

Baldwin also had one public interaction with Hannah Arendt that has been the subject of much debate. In 1962, when he published his essay “Letter from a Region in My Mind” in the New Yorker (which would later be published as the book The Fire Next Time), Arendt wrote to him, both praising this essay as a “political event of a very high order” but also challenging his “gospel of love.” She wrote: “In politics, love is a stranger, and when it intrudes upon it nothing is being achieved except hypocrisy.” She concludes that “Hatred and love belong together, and they are both destructive; you can afford them only in the private and, as a people, only so long as you are not free.”

I was baffled when I read this. I really didn’t know what she meant and I felt immediately defensive of Baldwin (my bias in his favor was undeniable). I wasn’t alone. Turns out many scholars have been weighing in on the question of who was right about love in politics: Baldwin or Arendt? I wanted to understand this conversation and consider what we could learn that was relevant for the Trump 2.0 era in 2025? That became the focus of my project and that’s what I’ll share, next time…

Thanks for reading!

I am very curious about what Arendt means here. She seems to define love as special preference (and also, wisely, as inextricable from its darker side, hate), while maybe Baldwin defines it in a more generous Christian sense, as an inclusive equalizer. Baldwin's conception of love is clearly very different than Arendt's conception of love. I look forward to reading the next installment!